Somalia confronts one of the globe’s most intricate and enduring humanitarian situations, stemming from a combination of conflict, climate impacts, disease occurrences, and mass displacement. Over thirty years of armed conflict have destabilized the health system, rendering it insufficiently equipped to address population requirements. The nation records some of the highest rates globally for maternal mortality, childhood malnutrition, and preventable diseases, complicated by inadequate health infrastructure, extremely low vaccination rates, and a severe deficit of healthcare professionals.

From January to September 2025, cholera infected over 8,180 individuals and resulted in nine fatalities (a case fatality rate of 0.1%), predominantly in regions with inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene conditions. Concurrently, a measles resurgence affected nearly 8,512 reported cases, primarily due to substantial numbers of unvaccinated children under five, widespread malnutrition, and limited access to basic healthcare in conflict-affected zones. A diphtheria outbreak further highlighted the breakdown of regular immunization programs, infecting more than 2,445 people – mostly unvaccinated children – and causing over 116 deaths. Additionally, flooding enabled the transmission of vector-borne illnesses such as malaria, dengue, and chikungunya into previously unaffected areas.

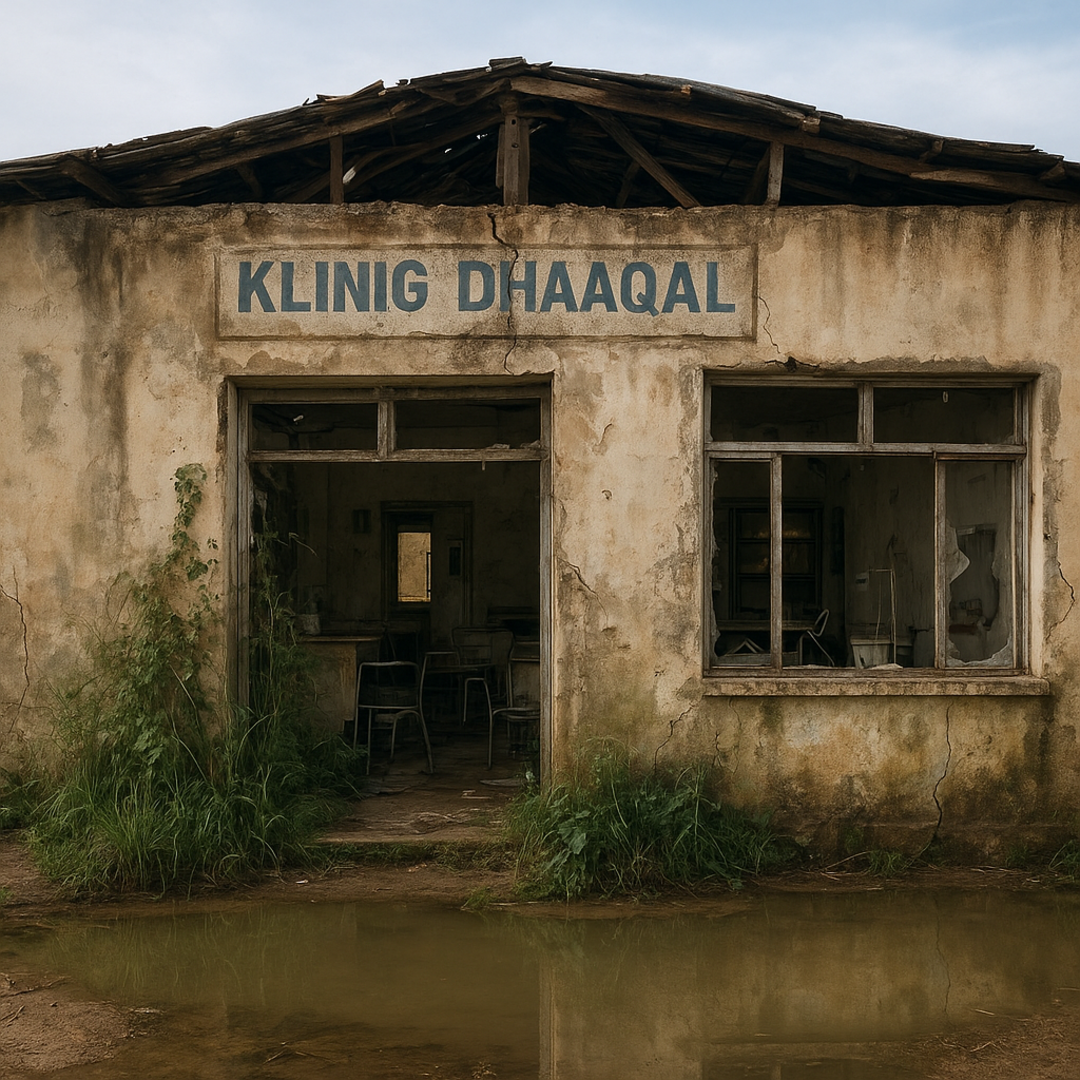

Furthermore, 95% of Somalia’s health budget relies on external financial support. Budget reductions indicate that 618 health facilities – 51 district hospitals, 413 health centers, and 154 primary health units – will probably cease operations in 2026. These establishments serve as vital resources, particularly in regions that are difficult to access, vulnerable to climate impacts, and report the highest malnutrition rates. Without renewed partner contributions, Somalia risks undermining significant public health achievements, increasing the probability of extensive disease outbreaks and preventable fatalities nationwide.

Humanitarian access worsened in 2025, especially in Lower Juba, Gedo, Hiraan, and Banadir, where conflict, inter-clan violence, and administrative barriers have restricted healthcare service delivery. Armed confrontations, road obstructions, and insecurity along primary supply routes impeded aid distribution and compelled more than 20 health facilities to shut down following advances by non-state armed groups. In multiple districts, movement limitations delayed the deployment of medical supplies and healthcare personnel, and these access restrictions continue to hamper WHO and partner activities.

Somalia’s Grade 3 emergency denotes the magnitude, complexity, and persistent severity of health requirements, necessitating system-wide reinforcement, guidance, and coordination. In 2025, nearly 6 million people required humanitarian and protection assistance, yet only 20% of the Humanitarian Response Plan (US$ 1.42 billion) was financed. Continuous investment will be essential to solidify advancements in epidemic control, maternal and child healthcare and nutrition, and to prevent the further decline of health outcomes in 2026.